In most WMS tasks the long trials essential to obtaining a high span score are also the later trials and thus are those most likely to be disrupted by PI.

Because PI can build up quickly across trials within a task ( Keppel & Underwood, 1962), items studied and recalled on early trials of WMS tasks can disrupt recall of items from later trials.

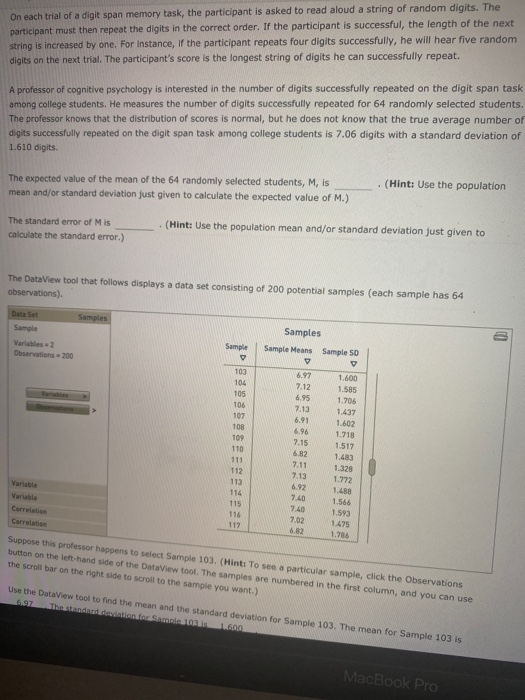

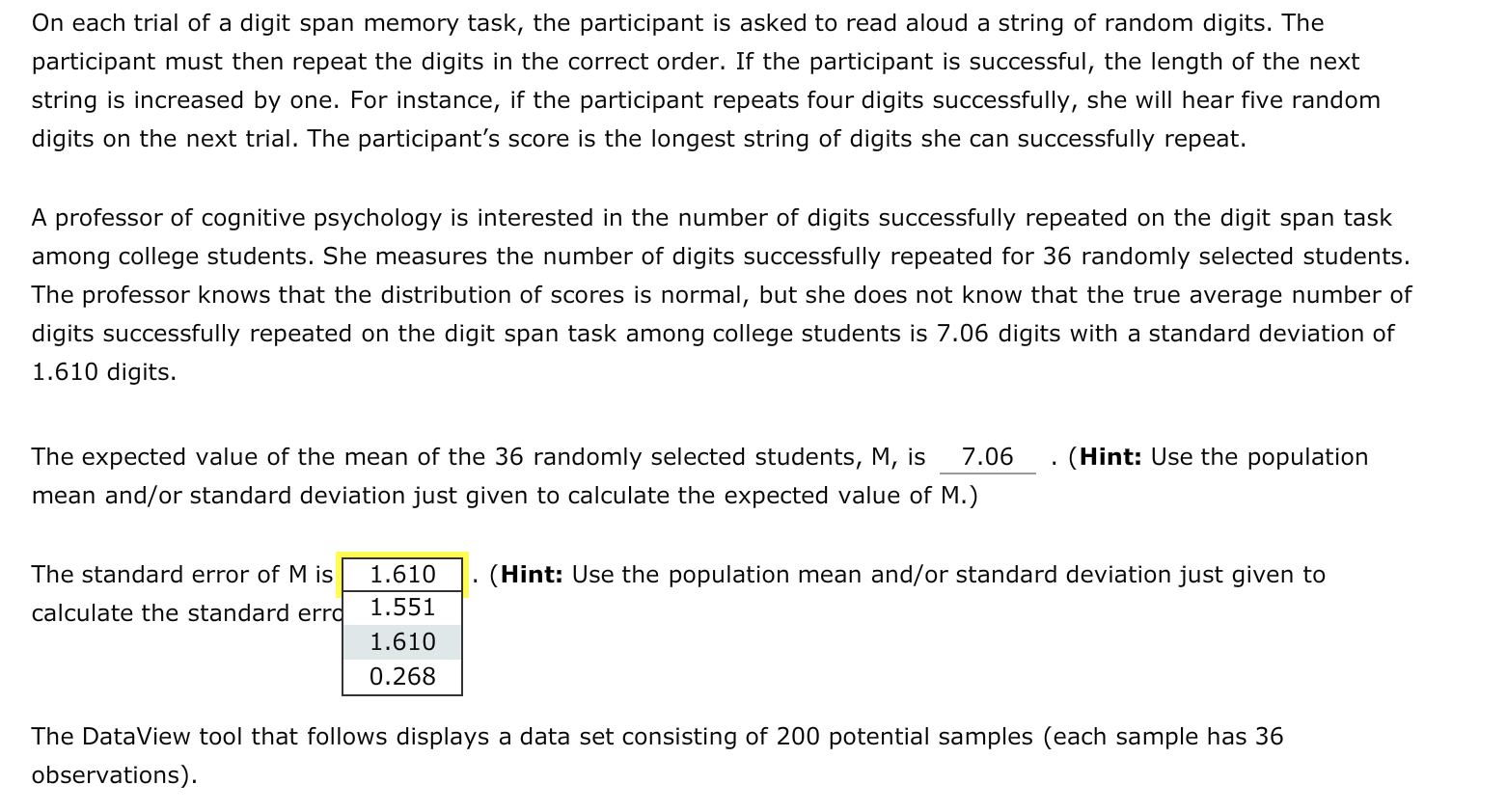

#HYPOTHESIS OF A DIGIT SPAN MEMORY TEST SERIES#

Likewise, young adults with high W19IM scores perform better on PI tasks than do those with low WMS scores ( Dempster & Cooney, 1982 Rosen & Engle, 1998).Īlso, a task analysis reveals that many WMS tasks unintentionally encourage the buildup of PI within the task because they consist of a series of study-recall trials that start with the shortest lists and end with the longest ( Dempster, 1992 May, Hasher, & Kane, 1999 Whitney, Arnett, Driver, & Budd, 2001). First, individuals and groups particularly vulnerable to the effects of PI (e.g., poor readers, young children, older adults) also perform poorly on span tasks compared with less PI-vulnerable young adults ( Chiappe, Hasher, & Siegel, 2000 Dempster, 1992). Several lines of work now suggest that PI also plays a major role in determining WMS scores. This decline in performance with increasing lists usually is attributed to proactive interference (PI), the generally disruptive effect of prior learning on the ability to retrieve more recently learned information. Recall of the target list declines from 75% to 25% as the number of previously learned lists increases, even when the target list uses words different from those in the previous lists ( Underwood, 1957 see also Keppel, Postman, & Zavortink, 1968 Zechmeister & Nyberg, 1982). Likewise, 24-hour delayed recall of a single, laboratory-learned list is dramatically affected by the number of lists learned in prior experiments. For example, for a series of lists learned over consecutive days, retention of the current day's list decreases as a function of the number of previous lists learned for both 5- and 48-hour retention intervals ( Greenberg & Underwood, 1950). Prior experience of this sort has large, detrimental effects on other memory tasks. The current study investigates the impact of participation in previous memory experiments on WMS. However, WMS measures are complex, and as a result it has been difficult to determine the cognitive components that influence the size of span scores and are responsible for their predictive power ( Baddeley, Logie, Nimmo-Smith, & Brereton, 1985 Tirre & Pena, 1992 Waters & Caplan, 1996). WMS tasks also predict performance across the life span, from childhood to at least middle age ( Siegel, 1994). Consistent with this view, WMS tasks predict performance on a range of skills including reading comprehension, text recall, and reasoning (see Daneman & Merikle, 1996, for a review). Both individuals and groups are thought to differ in this fundamental cognitive capacity. It is this capacity (in contrast to the capacity for simple, passive storage as measured by traditional span measures) that various working memory span (WMS) measures were devised to assess ( Daneman & Merikle, 1996). Working memory capacity is widely thought of as the mental workspace available for the simultaneous processing and storage of information ( Baddeley, 1986 Danemnan & Carpenter, 1980 Just & Carpenter, 1992).

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)